I bow humbly to my paternal and maternal grandmas who were and still are two of the most influential women in my life. I am what I am today because of what I have learnt from their life journey and would like to share small snippets of the same here. This is my tribute to the two most beautiful women who conquered life’s formidable challenges in their own sweet ways and left a lasting impression on me.

Mamma – My Dad’s Mum

“Are you a boy or a girl?” my eight year old curiosity blurted out. I was sitting at the bottom of the verandah step looking up at the face. Tightly curled, half black and half white chin hairs were quivering in the slight afternoon breeze and a dark shadow of a moustache curving the loop of her upper lip. That is the first time I am noticing my dad’s mum – Mamma, so closely.

“Don’t talk like that!” scolded my mum even before I finished my question.

“That’s alright. She is young.” adjusting the rough edges of her off-white plain khadi cotton sari covering her bald head, Mamma looked at mum who was sitting at the door to our bedroom. My Aunty was sitting on the step opposite at the door to their bedroom.

“She doesn’t understand – yet.”

It was 3.30 PM, I just arrived from school, and the maid was doing the dishes under the tap outside. A crow was on the edge of the stair case wall of our neighbor’s and was looking down with its head turned to one side so it can grab the food scraps thrown. Late afternoon sun was casting long shadows of the crow and the maid on the broken tile and cement yard under the verandah steps.

We were a joint family, 13 of us in that two large bedrooms, two kitchens, another smaller bedroom, a verandah, one bathroom and one toilet house of ours – six in my family and six in my uncle’s plus Mamma on the cot in the open bedroom of hers – a tiny corridor that separated the two bedrooms. The bedrooms were also the lounge rooms during day time. Her faded green iron trunk with two saris and a little tin with few coins and two rupee notes under her bed and a stool next to it with a jug of water and a stainless steel tumbler completed the furniture in her room – the corridor.

Her small frame was beginning to bend from the top of her back just below shoulders. She brushed the hair off my face with a shaky pointy finger twisted and knobby, bent in the middle. Circling the outline of my face down my cheeks, she said “I am a woman, darling.”

I have seen her struggle and wince many a times trying to straighten those bent and locked left middle and ring fingers with her shaking right hand. I didn’t know what it was but she shook continuously from head to toe, the only time she stopped was when she was asleep. I used to try hard not to laugh when her shaking hand missed her mouth and water from the tumbler spilled down her flat chest and drenched her. But I always ran to hold her hand to steady it from shaking. Mum and aunty used to take turns to spoon feed her meals, mostly rice and buttermilk as she couldn’t hold anything down.

“But, but, but…..” my voice trailed as I looked at her and then at my mum and aunty and back at Mamma.

Mum and aunty never covered their heads and often had jasmine flowers in their neat buns held by a black net. I never saw if Mamma had long hair or if she wore it in a bun or plaited it. Grey hairs normally peeked from under her sari that always covered her head. Today that grey hair is not showing from under Mamma’s sari either, only a shiny oily forehead receding back into where the hairline was. Mamma’s hollow eyes and sunken cheeks made her straight nose look even straighter without the eye getting distracted by the grey at the top. I bumped into a guy this morning as I was running out the front door. He had a small grey box in his hand. I often saw him sit under the tamarind tree around the corner on the street, shaving men’s beards and arm pits. I was late to school so I didn’t stop to question what the barber was doing walking into our yard. There is a whole wide world outside of my school, homework and music.

“That’s enough, go change and I will get you something to eat” mum’s command made me get up. I walked into our bedroom looking backwards at Mamma.

“She doesn’t know what to ask and what not…yet.” mum said to Mamma, her voice low and eyes downcast. What is that tone?

I didn’t then, but I know now that there is no simple word or a phrase in our language for saying ‘Sorry’ or for saying ‘I Love You’. These words and phrases are embedded in a very formal language structure and my mum only went up to grade three in primary school.

I still remember thinking why Mamma was like that if she was a woman, why wouldn’t she wear colorful saris like my mum or aunty, and have long hair plaited or up in a bun with flowers in them? Is she bald under that sari over her head?

Only years later did I realize that the man walking into our yard, the barber, was there to shave Mamma’s growing hair – as a widow from an orthodox Brahmin family she was not allowed to keep her hair, nor was she allowed to wear colored clothes, nor the red dot on the forehead, nor the kohl in the eyes, nor the flowers in her hair – lest she looks attractive for the lustful eyes of another man. My teenage brain struggled to comprehend the injustice and my increasing whys were only answered by ‘that’s the custom.’ That answer never satisfied me.

As a grown up I now understand that a woman’s life in India revolved around a man. Her beauty is the one unapologetic reason for a man to become an animal in quenching the thirst of his carnal desires. Before 1930’s, customs were such that when a woman’s husband died, regardless of her age, she was required to undergo the practice of ‘Sati’ where she was forced to sit on the open burning pyre of her husband’s body so what belongs to a man perishes with the man and doesn’t become an object of desire to other men. Sati practice was abolished by the late 1930’s and they couldn’t kill a widow legally since then. Instead, her hair was shaved off; she was not allowed to wear the vermillion dot between her eyebrows, the kohl in her eyes, no jewelry whatsoever and definitely not allowed to use turmeric and cream to beautify her skin. She was only allowed to wear plain white cotton khadi sari and was abandoned to the back of the house to grieve for the rest of her life, often for a man that she barely knew or loved and yet bore his children. She was not allowed to join in on family functions as it was considered to be a bad omen if a widow crossed one’s path and she was banned from eating spicy gourmet food, especially for dinner. Apparently food fuels one’s natural passions and a passionate woman was and still is a mortal danger to the society – a patriarchal rule. Second marriage was completely out of question and she will have to literally hide for the rest of her life even from her own children’s celebrations of milestones like birthdays and marriages. A living widow is as good as dead.

My grandma was widowed when she was barely 35 and ended up on her brother’s door step with nine kids, youngest a couple of months old and eldest, a daughter, 16 years old. My dad was 14, second eldest of the six girls and three boys. Mamma’s brother, a pharmacist and a well off farmer in a small rural town in the state of Andhra Pradesh in India, had only one son and took his sister and her brood in.

Mamma could do mental math faster than us who were attending school. She used to come up with answers before we finished saying the question out loud. She never attended school.

There was an incident narrated often to me and this apparently happened before I was born. I cherish that as it shows her strength. The wife of our neighbor, a prominent wealthy High Court Judge, apparently needed help in preparing green mango pickle that is made in large quantities to last the whole year. This was an annual ritual. So she sent word to my grandmother to come around with her daughters and daughter-in-law to cut the mangoes.

“Bring your kitchen knives with you” – was the message, an order than a request.

“Tell your madam to bring her knife and her mangoes and herself here to my place and we will gladly help.” Mamma’s reply back through their maid –Lack of riches had never put holes in the fence of dignity and self-respect she erected around herself and her family. My grandma was fearless.

I have never witnessed so much as raised voices between Mamma, my mum and aunty, neither was there any brotherly rivalry between my dad and my uncle. 13 people shared one bathroom and toilet with no alarm clocks, no open discussions each night about the morning timetables, nor were there any whiteboards or corkboards with announcements and notices, and yet there were no clashes. If the bathroom was occupied we waited and the next day we adjusted our own schedules. ‘First Understanding, Then Adjustment’ a saying of Sai Baba’s was role modeled by the adults in my life. When a sapling is protected, nurtured and nourished, it grows into a big strong tree gaining strength from its roots. Mamma is one of the most influential women in my life

Ammamma – My Mum’s Mum

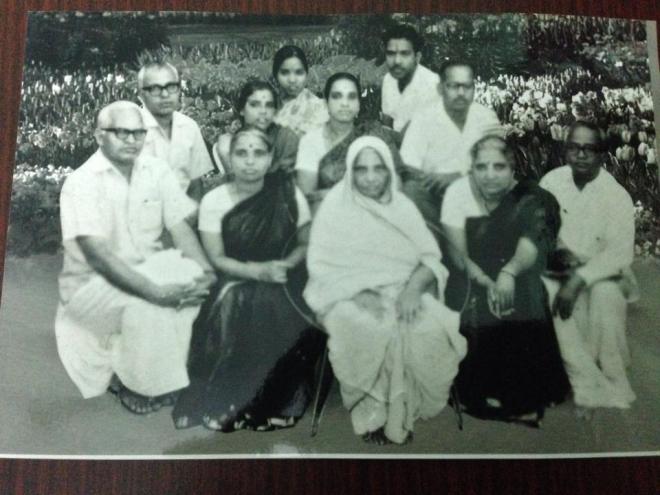

Short, stocky lady with a permanent pout, she is the most beautiful lady I know. She is the lady in the middle with the sari draped over her head. Ammamma had five daughters, my mum the eldest, sitting on to the left of Ammamma in the picture. She also gave birth to a boy who didn’t see life beyond two years.

Ammamma’s schooling story always brought a chuckle for me and I used to ask her to repeat it several times. It goes like this.

She was enrolled in the local government school in the tiny village of Narendrapuram in rural Andhra Pradesh. Chubby little Sundaramma at 5 held a big fat white chalk for the first time in between her fingers. Beaming from ear to ear, bent over her shiny new black slate, all eyes on the contours of the lines, she traced over the alphabet that her teacher wrote on that slate. In her mind she was writing the scriptures that her dad read every day. When the afternoon bell rang, carrying her slate and chalk in one hand and a little stick she picked up on the ground, Sundaramma skipped on the path amongst lush green paddy fields leading home for lunch. She hurried past a huge Neem tree and suddenly stopped, ran back, her 5 year old eyes wide, mouth slightly open in an ’O’, eyebrows raised, at the sight of buzzing bees busily building a hive. She went closer to the hive with her hand extended, fingers holding the pointy end of the stick, almost touching the little diagonal sticky looking pockets held together by buzzing and humming life, and pulled back. Went a bit closer than before, lingered a little longer and pulled back again. She checked the tip of the stick to see if any honey was on it. Her hand extended again towards the mass and before she knew lunged forward and the stick poked into one of the pockets. She pulled it out, examined the little sticky tip, and brought it to her lips, closed her eyes and slurped the dripping sweet honey. The distant humming became a sudden roar. She opened her eyes and raised her head. One furry winged little brown thing landed on her forehead, she raised her hand from her mouth to shoe it off even as she felt a little prick. Two more landed on her raised arm. As the pain started to register, she dropped her slate to use the left hand to get rid of the sticky creatures first on forehead, next on the right arm, but by this time there were more of them swarming around, circling her buzzing, finding random spots on her face and hands without discriminating. Little Sundaramma started running screaming, her slate left at the bottom of that big tree, ‘A’ in Telugu, the first letter of the alphabet staring back in disbelief, stretched in agony like her mouth. She ran through the front door, her eyes swollen shut, lips, nose and cheeks all blended into each other, hard to tell what began where. Her father looked up at her from the afternoon ritual of chanting the sacred scriptures before lunch, his mouth stuck open in between the lines, eyes widened as he took in his daughter’s face. He lunged up from his seat, pulled her towards him, questioning what happened whilst examining her face closely. Between sobs Sundaramma narrated what happened. Even before she finished her sentence, he pushed her away from him, ordered her to go and wash her face and stay home – no need to go back to school – Ever!

Sundaramma didn’t know what hurt most – the bee stings or loss of school. Her schooling finished before it began.

Ammamma was married at 14 and had my mum by the time she turned 16. She became a widow at 35 when my grandfather died in an accident in 1946. My mum at that time would have been 18, already had my eldest brother who was two years old. My mum’s youngest sister was a year or two older than my brother.

Ammamma had a habit of bending down instead of sitting to cook as the stove was on the floor. Here is a story that I made her tell me every second day as not only was it funny but also showed her strength to stand up to male domination. Apparently, one morning she was busy cooking lunch to pack for her husband and suddenly felt something thumping her backside. She slowly turned around and saw that Grandpa was standing behind her, fully dressed in his crisp white pants and shirt, ready to go to work. He was running late. Instead of saying something, he started hitting her with his umbrella because packed lunch was not ready.

There was a bucket of water next to her. Shouting “Why are you hitting me, you bastard?” she lifted the bucket and threw the water on him. Fully drenched and a stunned Grandpa apparently left for work without saying a word.

He never hit her again after that.

Life never thwarted Ammamma’s desire to learn to read and write. In her mid-50’s she demanded her youngest daughter teach her how to write her name, just her name, so she can sign the pension papers with a pen, not an ink pad. Luckily for Ammamma, Grandpa was an accountant in Auditor General’s office, so she was eligible for a pension on his death. She used that ink pad for over 15 years and hated the black mark leaving a stain on her right thumb month after month for days on end.

She signed the official papers for the first time with a pen and showed us her signature. Big, crooked and wavy letters complete with a missing alphabet in her name – she signed Sundamma. We laughed, but she beamed, eyes shining bright.

She defeated the male dominance – finally.

She may not have been formally educated but her thirst for knowledge was unquenchable. She would bring the newspaper daily to one of us and insist we read it to her. The most important news she wanted to hear was if there was a rise in pension for the widows of employees of Accountant General’s office. We kids would refuse her that little pleasure and make fun of her curiosity and pretend to scan the newspaper, knowing that those things cannot be a daily occurrence. She never took offence. Sundaramma passed away in sleep one night in 1989 and I never had a final glimpse of her.She taught me that innocence & curiosity are priceless possessions that protect one from life’s twists somehow.

Padma, this is unflinchingly and beautifully real. A necessary and inspiring book, most definitely. In the meantime, you are offering a most poignant glimpse into a culture that we should all be so lucky to see. What a gift. Please keep going….!!

LikeLike

Thanks Amy…Our writers’ group is an inspiration indeed for me.

LikeLike